STANDING COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE POLICY

A REPORT ON THE MODERNIZATION OF THE BAIL SYSTEM: STRENGTHENING PUBLIC SAFETY

1st Session, 43rd Parliament

1 Charles III

ISBN 978-1-4868-6871-1 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-4868-6872-8 [English] (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-4868-6874-2 [French] (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-4868-6873-5 [English] (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-6875-9 [French] (HTML)

The Honourable Ted Arnott, MPP

Speaker of the Legislative Assembly

Sir,

Your Standing Committee on Justice Policy has the honour to present its Report and commends it to the House.

|

|

|

Lorne Coe, MPP

Chair of the Committee

Queen's Park

March 2023

STANDING COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE POLICY

MEMBERSHIP LIST

1st Session, 43rd Parliament

LORNE COE

Chair

SOL MAMAKWA

Vice-Chair

ROBERT BAILEY NATALIA KUSENDOVA-BASHTA

STEPHEN BLAIS BRIAN RIDDELL

CHRISTINE HOGARTH BRIAN SAUNDERSON

TREVOR JONES JENNIFER (JENNIE) STEVENS

Chatham-Kent—Leamington

VINCENT KE KRISTYN WONG-TAM

JESS DIXON AND JOHN VANTHOF regularly served as substitute members of the Committee.

THUSHITHA KOBIKRISHNA

Clerk of the Committee

ANDREW MCNAUGHT

Research Officer

Contents

Arguments Against More Restrictions 6

Proposals to Amend the Criminal Code 7

Section 95 and Other Firearms Offences 9

Judges, not Justices of the Peace 10

A New Community Corrections Compliance Unit 16

Centralized Oversight/Province-Wide Standards 17

Ministry of the Attorney General 17

Indigenous Peoples and Bail 19

Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services Corporation 19

Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service 19

Congress of Aboriginal Peoples 20

Recommendations for the Government of Canada 22

Recommendations for the Government of Ontario 23

Appendix A: Committee Motion 25

Appendix B: Premiers’ Letter to the Prime Minister 27

INTRODUCTION

On December 27, 2022, Ontario Provincial Police Constable Grzegorz Pierzchala was shot and killed while responding to what appeared to be a routine roadside check near Hagersville, Ontario.

Earlier that day, the rookie officer found out that he had passed his 10-month probationary period with the police service.

Constable Pierzchala was 28 years old. He was the fourth Ontario officer to be killed in the line of duty during the closing months of 2022.

According to publicly available information, one of the two individuals arrested and charged with Constable Pierzchala’s murder has a significant history with the criminal justice system, and of violent behaviour generally. Notably, this history includes

· a conviction and prison sentence for armed robbery, and a life-time ban on possessing a firearm in 2018;

· outstanding charges for assault and weapons offences committed in 2021; and

· an outstanding arrest warrant issued in September 2022 for failing to make a court appearance.

Although bail for the charges laid in 2021 was initially denied, it was granted following a review. The suspect was free on bail at the time of the shooting.

OPP Commissioner Thomas Carrique described Constable Pierzchala’s murder as “preventable,” and said that he was “outraged” at the fact that someone with the suspect’s history had been able to make bail. The Commissioner also said that “something has to change.”

Only weeks before, in October 2022, the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers of Justice and Public Safety had met in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. That meeting led to “a clear and unified call to action for the federal government to reform Canada’s bail system.”

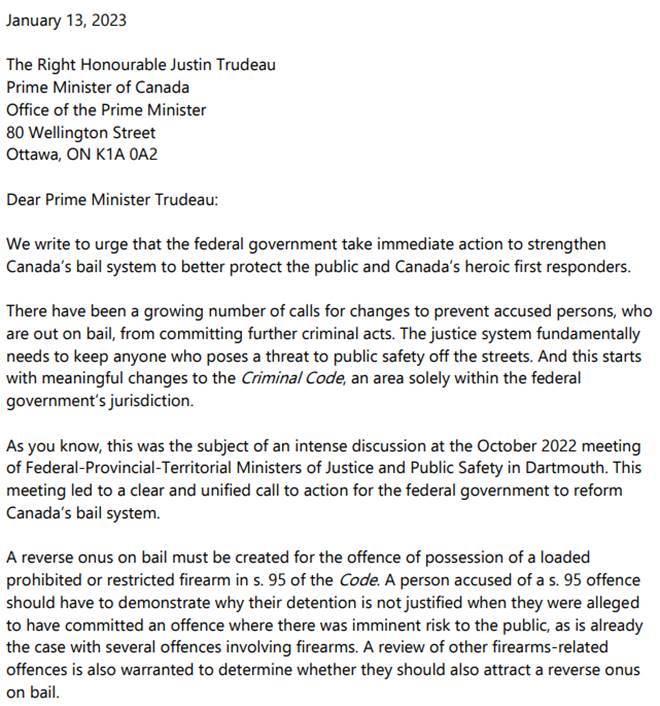

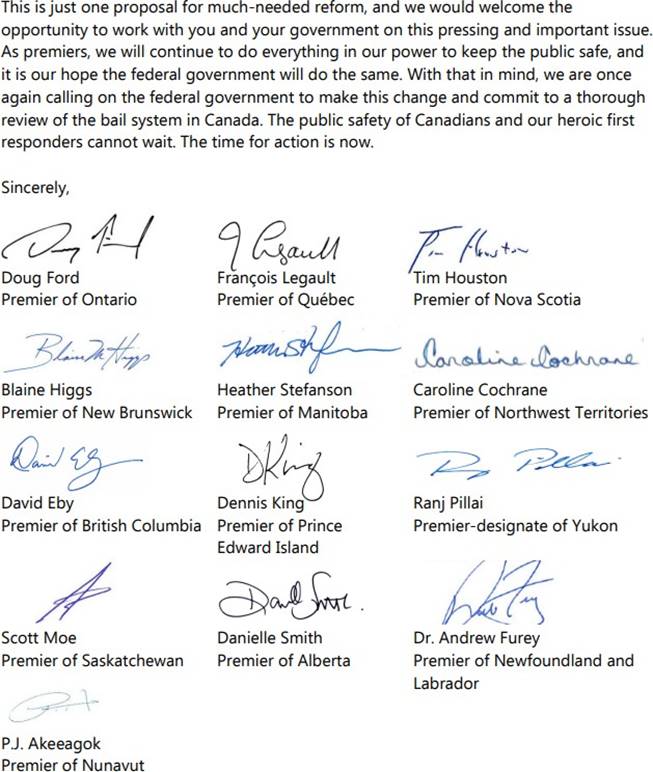

On January 13, 2023, the premiers of the 10 provinces and three territories wrote a letter to Prime Minister Trudeau, again urging the federal government to take immediate action to strengthen Canada’s bail system. In addition to a general review of firearms offences to determine which ones should be designated as “reverse-onus” offences for bail purposes, the premiers proposed a specific amendment to the Criminal Code that would establish a reverse-onus on persons charged with the offence of possession of a loaded prohibited or restricted firearm when seeking bail. (Appendix B is a copy of the premiers’ letter)

On January 18, 2023, the Standing Committee on Justice Policy passed a motion pursuant to Standing Order 113(a) to conduct a study on the reform of Canada’s bail system as it relates to the provincial administration of justice with regard to persons accused of violent offences or offences associated with firearms or other weapons. (Appendix A)

This report is based on the testimony received during two days of public hearings held in Toronto on January 31 and February 1, 2023, as well as written submissions received as of the Committee’s deadline. It reflects presentations from a range of organizations and individuals, including the Commissioner of the OPP, chiefs of police, police associations, police services boards, civil liberties and correctional reform groups, organizations representing the criminal defence bar, academics, and Indigenous groups. (Appendix C is a list of witnesses)

The Committee wishes to express its appreciation to all the witnesses who took the time to make presentations or prepare written submissions.

In submitting this report, the Committee recognizes that there are many longstanding issues associated with bail reform. Among these are the fact that on any given day more adults are in custody awaiting trial than there are convicted offenders serving time, and that there is evidence to suggest that disadvantaged groups such as Indigenous people, persons with mental health problems, and low income individuals are less likely to get bail.

While legislators will need to carefully review these and other issues, our concern is with what can be done now to enhance the protection of police officers and the public at large. Accordingly, the Committee is making two sets of recommendations:

· Recommendations directed at the federal government to amend the Criminal Code to strengthen the bail system as it applies to those charged with violent offences or offences in which firearms or other weapons are involved.

· Recommendations directed at the provincial government to make changes to the administration of justice system that will improve the functioning of the bail system in Ontario.

BAIL REFORM

The Need for Reform

All of Ontario’s policing leaders are unanimously agreed that bail reform would save lives. Constable Pierzchala’s death, they say, was not an isolated incident; moreover, it was the inevitable result of a bail system that has not been working for many years.

According to OPP Commissioner Thomas Carrique, incidents involving offenders with a history of violence who commit further crimes while on bail are “not rare.” In fact, the problem was identified almost 15 years ago by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, which passed a resolution in 2008 calling on the federal government to strengthen bail and sentencing laws to protect the public from offenders “who have clearly demonstrated their unrelenting willingness to engage in criminal behaviour that directly harms other citizens.”

Commissioner Carrique stressed that, as in 2008, it is a minority of offenders who commit most of the crimes in Canada. Yet, despite the passage of almost 15 years, “no meaningful action has been taken” to address the fact that the danger to the public posed by this small group of offenders “is not adequately recognized” in our bail and sentencing practices.

Commissioner Carrique told the Committee that he has written to the federal Minister of Public Safety, Marco Mendicino, asking him to consider “meaningful bail reform” that would address the threat to officers and public safety posed by repeat violent offenders charged with violent, firearms-related offences who are being released on bail.

To highlight the urgency of the situation, Commissioner Carrique asked the Public Safety Minister to consider the known facts relating to one of the suspects arrested for Constable Pierzchala’s murder. These facts include:

· the suspect has a violent past, with criminal convictions for armed robbery using a firearm, assault with a weapon, possession of a weapon and assault;

· the suspect had been subjected to a five-year weapons prohibition in 2015, a 10-year weapons prohibition in 2016, and another 10-year weapons and lifetime firearm prohibition in 2018;

· at the time of Constable Pierzchala’s death, the suspect was under bail conditions prohibiting him from possessing a weapon and ammunition;

· these conditions stemmed from a 2021 incident that included allegedly assaulting three victims, one of them a peace officer; possession of a prohibited weapon while prohibited from doing so; unauthorized possession of a firearm; carrying a concealed weapon; possession of a firearm with an altered serial number; careless use, carry, transport or storage of a firearm; and mischief and assault charges;

· the suspect had a record of five previous convictions for failing to comply with a court order; and

· the GPS ankle monitoring device he had been ordered to wear while under the supervision of a surety had been discarded.

“Despite all of this,” the Commissioner said, the suspect was released following a bail review.

We also heard from the police associations representing thousands of police officers across the province, who expressed their members’ frustration with what they see as a “catch-and-release” approach to bail. John Cerasuolo, president of the Ontario Provincial Police Association, read the following excerpt from an email he received from a retired sergeant who worked in northern Ontario:

Catch and release is a very appropriate phrase describing what is happening out there. Over the many years, many of my officers have complained bitterly to me about having to apprehend the same criminals time after time when the criminals were once again

released, rather than being held in custody until their charges were dealt with.

According to Mark Baxter, president of the Police Association of Ontario, not only does the catch-and-release approach to bail place inadequate emphasis on protection of the public, it encourages escalating violent behaviour:

Our members are frustrated to work within a system that is not prioritizing community safety. They are frustrated by apprehending a known offender one day and being called on their next shift to the same place, for the same reason, to arrest the same person. . . Too often, with each release, the offender’s behaviour has worsened, and their negative choices emboldened, until the day comes that the individual becomes violent, or more violent, and the result is that someone in our community is injured or killed.

Similarly, Jon Reid, president of the Toronto Police Association, said that the members of his association are “beyond frustrated.” He related an incident from 2021, in which armed bank robbers seriously injured two plainclothes police officers during the arrest of the suspects. One of the accused was released on bail within 24 hours, “before both officers were released from hospital.” Commenting on this incident in an op-ed piece, Mr. Reid concluded:

If our bail system is designed and/or interpreted to justify releasing individuals in these circumstances, what message does this send to the community that they’re serving? The simple answer is this: it sends the wrong message to the people who protect our communities and those who seek to live in a peaceful and just society. It erodes confidence in the administration of justice.

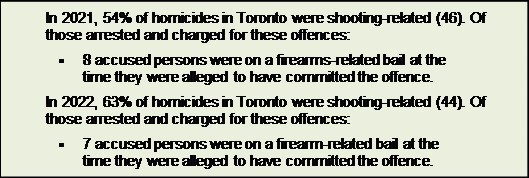

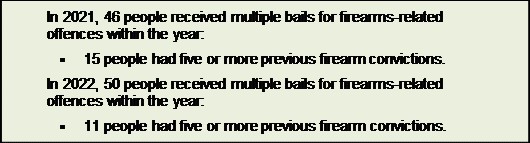

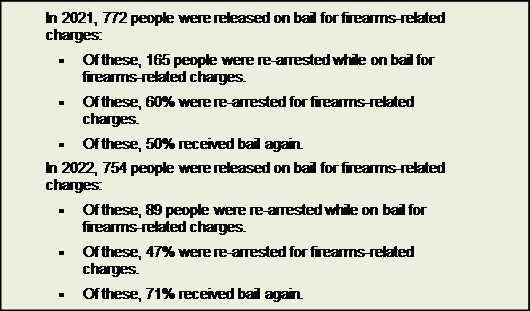

Empirical evidence presented by Myron Demkiw, Chief of the Toronto Police Service, appears to support the observations of frontline officers. The Chief presented the following numbers to the Committee:

Chief Demkiw acknowledged that the cases reflected in these figures represent unproven allegations. Nonetheless, he said the data is strongly suggestive of a link between firearm bail and public safety that “calls out for urgent action.”

Commissioner Carrique also presented data collected by the OPP linking bail and violent crime. For the years 2021 and 2022, 587 repeat violent offenders who were free on bail committed bail violations that resulted in 1,675 charges for failing to comply. Of those 587 violent offenders, 464 were involved in serious violent crimes while out on bail; 56 of these serious violent crimes involved a firearm. In the Commissioner’s view, “these figures are concerning and express an immediate need for change.”

Another aspect of bail reform highlighted during our hearings is the impact tragic incidents like Constable Pierzchala’s death is having on both officer morale and the ability of police services to recruit new officers.

According to the OPP Commissioner, these incidents are taking a “devastating” toll on the psychological well-being of officers. Moreover, the current situation has created “the most challenging time in my 33-year history with recruiting police officers.”

The president of the Police Association of Ontario also addressed the issue of officer morale:

It’s having a big impact on morale. Our members are frustrated. They’re tired, and in a lot of circumstances, they’re worried, they’re concerned. The four police officers who were killed in Ontario in the last four months were all ambushed. They were killed because they were wearing a uniform, and they were specifically targeted. As we learn more details of [these deaths] we know that could have been any police officer. . . So that has an effect, and that has an effect on members’ well-being and on their mental health as well. This creates anxiety around going to work, and what are you going to walk into.

Arguments Against More Restrictions

Several witnesses offered a different perspective on bail reform. These presenters included criminal defence lawyers, civil liberties and correctional reform groups, community service providers, mental health organizations, and academics.

Additional statutory bail restrictions, they said, would only be counter-productive. Moreover, any reforms that are made should be based on solid evidence.

They argued that in any event, further restrictions are not needed. Contrary to the perception created in the media, current bail law and practices are “not lenient.” The Criminal Code already includes several reverse-onus provisions for offences involving firearms and intimate partner violence, and already allows for pre-trial detention for the purpose of ensuring public safety. Ontario’s Crown Prosecution Manual, it was noted, directs Crown prosecutors to seek detention for any firearms charges.

Statistics on the number of people held on remand in Ontario jails were also cited as evidence of how the bail system has become more, not less, strict. In the 1980s and 1990s, pre-trial detainees represented 23%-30% of the prison population. Today, remand prisoners account for more than 70% of all inmates held in Ontario’s correctional system. Ontario was said to have one of the highest proportion of such inmates.1

New bail restrictions, it was argued, would also exacerbate long-standing inequalities in the criminal justice system. In particular, we were asked to consider the fact that Black and Indigenous people, as well as individuals experiencing poverty, homelessness and mental health issues, are already overrepresented in admissions to pre-trial detention. Black adults represent 5% of the adult population in Ontario, but 14% of admissions to custody. Indigenous

1 According to Statistics Canada, the adult remand population in Ontario correctional facilities in 2020-2021 was 77% of all adults in custody (remand and sentenced custody). Historical data shows that from the 1980s to the late 1990s, remand percentages ranged from 20% to 39%―see Statistics Canada, Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2018/2019 (December 21, 2020) and Average counts of adults in provincial and territorial correctional programs (April 20, 2022).

people account for 2.9% of the population, but 17% of custodial admissions.2 There is also evidence suggesting that people with no fixed address are more likely to be denied bail. Stricter bail laws, it was argued, would only result in further over-representation of these groups in detention, and would run contrary to efforts to reduce systemic discrimination.

As noted by the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies (CAEFS), the Office of the Chief Coroner recently released a report on conditions in Ontario jails which identified overcrowding, mistreatment, and lack of supports and programming. According to the CAEFS, these findings make it difficult to argue that holding more people in pre-trial custody would enhance public safety; rather, it would have the potential to cause significant harm to individuals and the public. In her written submission to the Committee, Dr. Jennifer Foster states that being held in detention forces inmates to “harden” in order to cope, and that, “whether convicted or not,” hardening continues to happen after release, requiring further support and treatment to recover from detention.

Witnesses stressed that our criminal justice system cannot be expected to eliminate all risk. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) pointed out that a pattern of breaching court orders does not necessarily mean dangerousness―yet we continue to release people on bail conditions such as curfews, prohibitions against returning to home, and bans on possessing drugs and alcohol. According to the CCLA, people who fail to comply with court orders often do so, not because they disrespect the court, but because they are struggling to survive. Such restrictions, it was argued, almost guarantee failure.

Finally, the Committee was urged to consider that, for young people in particular, rehabilitation and reintegration are the key to the long-term protection of the public. Achieving these objectives requires speedy resolution of youth cases, as well as access to community services and family.

PROPOSALS TO AMEND THE CRIMINAL CODE

Under the Canadian constitution, the federal government has exclusive power to enact criminal law, including “the procedure in criminal matters.”3

Bail is a matter of criminal procedure. Accordingly, any legislative reforms relating to bail fall within federal jurisdiction.

The recommendations for amending the Criminal Code discussed in this section are directed at the federal government for immediate action.

2 Statistics Canada reported that in 2020-2021, “Black adults made up about 5% of the adult population in Ontario, but they accounted for 14% of admissions to custody and 8% of admissions to community services in that province”―see Overrepresentation of Black People in the Canadian Criminal Justice System (December 15, 2022). In 2021, Indigenous people accounted for 2.9% of Ontario’s population and 17% of custodial admissions―see Census Profile 2021 (February 1, 2023) and Adult custody admissions to correctional services by Indigenous identity (April 20, 2022).

3 Constitution Act, 1867, s. 91(27).

Reverse-Onus Offences

The general rule under the Criminal Code is that the prosecution (the Crown) must prove to a judge or a justice of the peace that pre-trial detention of an accused is justified on one or more of three grounds.

In particular, the onus is on the Crown to establish that detention is necessary

· to ensure the accused’s attendance in court;

· for the protection or safety of the public; or

· to maintain confidence in the administration of justice.4

On the other hand, the Code has always (at least, since the bail system was modernized in the early 1970s) recognized that there are circumstances where the onus should be on the accused to show why they should be released back into the community while awaiting trial. The list of so-called “reverse-onus” offences has grown over the years, and currently includes where an accused is charged with

· first or second degree murder;

· an indictable offence committed while out on bail for another indictable offence;

· trafficking in firearms;

· discharging a firearm recklessly or with intent to wound or endanger life;

· attempted murder, robbery, or sexual assault using a firearm;

· an offence involving a firearm or other prohibited or restricted weapon, committed while under an order prohibiting the person from possessing such a weapon;

· an offence in which violence was used or threatened against an intimate partner, and the accused was previously convicted of an offence in which violence was used or threatened against an intimate partner; and

· a bail offence (failing to comply with conditions of release).5

The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that a statutory reverse-onus provision―on its face―amounts to a denial of bail, contrary to section 11(e) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Section 11(e) provides that anyone charged with an offence has the right “not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause.”

4 Criminal Code, s. 515(10)(a)-(c).

5 Criminal Code, s. 515(6).

The Supreme Court has also said, however, that a reverse-onus provision is nonetheless constitutional if it meets the “just cause” requirement of section

11(e). In the 1992 case of R. v. Morales, for example, the court unanimously upheld the Code’s reverse-onus provision for cases where an accused is charged with committing an indicatable offence while on bail awaiting trial for another indictable offence.6

Section 95 and Other Firearms Offences

In their letter to the Prime Minister of January 13, 2023, the 13 premiers proposed the following amendment to the Criminal Code:

A reverse onus on bail must be created for the offence of possession of a loaded prohibited or restricted firearm in s. 95 of the Code. A person accused of a s. 95 offence should have to demonstrate why their detention is not justified when they were alleged to have committed an offence where there was imminent risk to the public, as is already the case with several offences involving firearms.

Section 95 of the Code makes it an offence for a person to possess, “in any place,” a loaded prohibited or restricted firearm, or an unloaded prohibited or restricted firearm together with readily accessible ammunition, unless the person has an authorization or licence that allows possession of the firearm at that particular place and a registration certificate for that firearm.

All of the policing community leaders appearing before the Committee expressed their support for the premiers’ proposal to add section 95 to the Code’s list of reverse-onus offences, as well as for expanding the list to include other offences that pose a substantial risk to public safety.

Whether the premiers’ proposal regarding section 95 would meet the Charter’s “just cause” standard is a matter for the federal Department of Justice to assess. Police witnesses suggested that it would, given that the proposed amendment is limited in scope (it would target only a small group of offenders) and would promote a legitimate public policy objective (public safety).

Repeat Violent Offenders

As noted in our discussion on the need for reform, the OPP Commissioner highlighted a resolution passed at the 2008 meeting of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP), in which the Association proposed amendments to the Criminal Code that would address the fact that a small number of offenders commit most of the violent crime in Canada.

The stated purpose of those amendments is to “redress the incorrigible behaviour of many individuals who, over a significant period of time, have demonstrated that they will continue to victimize others regardless of any bail conditions imposed on them or sentences handed out pursuant to current sentencing practices.”

6 R. v. Morales, [1992] 3 S.C.R. 711.

In particular, the CACP resolution proposed the following amendments:

· a definition of “chronic offender,” based on a threshold number of offences committed over a set period of time;

· a presumption that chronic offenders satisfy the secondary and tertiary criteria for pre-trial detention set out in section 515(10)(b) and (c) of the Code (i.e., that detention is necessary for the protection or safety of the public, and to maintain confidence in the administration of justice);

· placing the onus on “chronic offenders” to show cause why they should be granted bail; and

· eliminating the sentencing principle that requires judges to consider alternatives to incarceration in cases involving chronic offenders, and providing for enhanced sentences of incarceration for chronic offenders for the purpose of decreasing victimization.

Commissioner Carrique said that the recommendations contained in the CACP resolution remain relevant today. He noted, however, that the term “repeat violent offender” has largely replaced “chronic offender,” and that the current focus of the proposal is on firearm offences and violence against intimate partners.

Judges, not Justices of the Peace

With the exception of a few serious offences, the Criminal Code provides that bail hearings may be conducted in front of either a provincial court justice (i.e., a judge) or a Justice of the Peace (JP).

Unlike a judge, JP’s are not required to have formal legal training. As a result, some JPs are lawyers, some are not.

In Ontario, the vast majority of bail hearings are conducted in front of a JP, not a judge. Several witnesses argued that JPs who lack formal legal training might not be well-positioned to assess all of the legal issues arising out of a bail decision involving violent offenders accused of serious crimes. Jim MacSween, president of the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police, observed that he has always been “struck” by the fact that “the most complex and violent crimes are placed before a justice of the peace.”

One of the recommendations that has been submitted to the federal government by Chief Demkiw and the Toronto Police Services Board calls for an amendment to the Criminal Code that would make it mandatory for bail hearings involving serious firearms offences (“around a dozen, maybe 13 offences”) to be heard by a superior court judge, or at least by a provincial court judge.

Chief Demkiw explained that, while the law currently allows for judges to be assigned to these types of bail hearings, this is generally not the practice in Ontario. Making this mandatory under the Criminal Code, he said, “would clearly convey Parliament’s view of the seriousness of these offences and the impact that these offences have on our communities.”

According to the Chief’s and the Board’s estimate, their recommendation would affect a small volume of cases, and the courts could easily manage the additional case load.

In connection with this recommendation, the Committee was made aware of two pilot projects. As described by the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, under a pilot project in Ottawa, all bail hearings were heard by an Ontario Court judge. Today, JPs are again handling bail hearings, although they are able to transfer to a judge, if available. A similar project was implemented at the College Park courts in Toronto.

Anecdotally, we heard that both projects succeeded in making bail hearings more efficient, and provided both parties (Crown and defence counsel) with a better understanding of the issues.

Groups such as the Criminal Law Association and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, as well as other members of the criminal defence bar, indicated their support for having judges preside over bail hearings. In their view, judges have the training and experience necessary to navigate the legal arguments that are made in bail court, something that many JPs simply do not have.

The Committee also heard that other jurisdictions across the country regularly assign judges to bail court. Although there are advantages to this approach (as noted above), one of the downsides is cost―the salaries of judges are significantly higher than those for JPs.

One witness said that they have been unable to obtain any evaluations of the two pilot projects from the Ministry of the Attorney General, and suggested that the Committee follow up on this.

We understand that such a report was prepared in 2020. If that report is publicly available, we ask that the Ministry forward a copy to the Committee at its earliest convenience.

In conclusion, we note some of the Committee’s discussion around the Ministry of the Attorney General’s “guns and gangs” bail program, introduced in 2018.

Under the program, a “legal SWAT team” is assigned to provincial courthouses in Toronto. Each team is led by a Crown Attorney responsible for ensuring that violent gun criminals are (as a general rule) “denied bail and remain behind bars.” A team of bail compliance officers is responsible for ensuring that those who are released on bail comply with the conditions of their release.

A number of witnesses appearing before the Committee said they support expanding the Ministry’s bail program to include chronic violent offenders. These witnesses included Toronto Police Chief Demkiw, as well as Chief MacSween of the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police, who said that “we do a great job around guns and gangs . . . anything the government can do to create a more efficient and more effective way of monitoring people on bail would be a welcome addition.”

Jon Reid of the Toronto Police Association, who noted that he has direct experience with guns and gangs programs, stressed the benefits of having specialized personnel with “intimate knowledge” of firearms offences who can assist judges and JPs at bail hearings. He also noted that the “integration” of Crown Attorneys and police officers in Toronto has allowed for a better sharing of information, including photographs of the types of weapons involved in these cases. “Once you actually bring that [photographs] to court and the courts see it,” he said, “I think people start to take notice more and it gets their attention.”

Cash Bail

Under the Criminal Code, one of the release orders a JP or a provincial court judge may make at a bail hearing is a “recognizance.” A recognizance is a promise by the accused to attend in court as required, and to comply with any conditions set by the court.

A recognizance also includes a financial component. If the accused fails to attend in court or abide by release conditions, the accused or their surety will be indebted to the court in a specified amount.

There are four main types of recognizance orders:

· the accused is released “on their own recognizance,” with a promise to pay an amount to the court if they breach the release order;

· the accused is released with a surety (a person who agrees to supervise the accused while on bail) who pledges to pay an amount to the court in the event the accused breaches the release order;

· the accused is released without a surety, but with a cash deposit (“cash bail”); or

· the accused is released with both a surety and a cash deposit.

If the accused has been released on their own recognizance, they are personally liable for the amount specified in the release order. If there is a surety (or sureties), they are responsible for any amount pledged to the court.

In 2017 the Supreme Court of Canada stated in R. v. Antic that a recognizance with a financial pledge is “functionally equivalent to cash bail and has the same coercive effect.” Accordingly, cash bail should be relied on only where release on a recognizance with sureties is unavailable.7

Police officers experienced in bail matters said that they disagree with the Supreme Court’s assessment that a recognizance with a pledge and cash bail are equally coercive. The president of the Police Association of Ontario (PAO), for example, said, “this is not true . . . the reality of the situation is that the Crown and the court never seize the surety’s property, and the accused individuals know this.” The result, he said, is that a pledge by an accused or a surety under a recognizance has no coercive effect at all―the accused might as well be released “on a mere promise to appear.”

7 R. v. Antic, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 509.

The PAO recommended that, “if the Crown and the courts continue to be unwilling to seize assets,” the Criminal Code should be amended “to place a greater emphasis on cash deposits.” Such an amendment, it was argued, would make those who have been released on bail more likely to comply with their conditions and is justified in the case of chronic offenders arrested in possession of a weapon.

Women in Canadian Criminal Defence, a national advocacy organization for women, noted the argument against the PAO’s proposal:

To be clear, the Canadian bail system is premised on the fact that we do not require cash for bail, because that would create a classed system . . . we need to recognize that whatever reforms we put in place on bail are going to have a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged groups.

ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE

Under the Canadian constitution, provincial legislatures are responsible for the “administration of justice” within their respective jurisdictions.8

In Ontario, the Ministry of the Attorney General oversees the administration of justice, which is defined as the provision, maintenance, and operation of the courts, the offices of Crown Attorneys, and jails.9

As a result, while the federal government is responsible for enacting criminal law and procedure, including the law of bail, the provinces and territories are responsible for providing the “infrastructure necessary to deliver this law on the ground.”10

The discussion and recommendations in this section are directed at the provincial government for its consideration.

Bail Monitoring

Over the course of our hearings, it became apparent that there is no single entity responsible for ensuring that people out on bail are complying with their bail conditions―police play a role, as do sureties and community supervision programs such as the John Howard Society’s bail beds program. This section reviews the testimony we received on how various aspects of the current bail monitoring system are working today, and notes a proposal to create a new oversight model.

8 Constitution Act, 1867, s. 92(14).

9 Administration of Justice Act, s. 1.

10 Gary T. Trotter, Understanding Bail in Canada (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2013), p. 7.

Police

The Committee heard that the police do monitor people who are on bail. An example is York Region’s high-risk offender unit, which checks compliance with bail conditions for those posing the greatest risk to the community. The Region also has an intimate partner violence unit that monitors people on bail.

We also heard that the police have the authority and responsibility to apprehend those who violate their release conditions, and may seek an arrest warrant for this purpose from the courts.

Given the demand on resources, however, the reality is that police services cannot give bail enforcement the attention it deserves. Police representatives noted that dedicated police bail enforcement units across Ontario have been disbanded, with members being redeployed to front line emergency response. In jurisdictions where there are no dedicated units, the police simply do not have the time to do bail checks consistently. Accused persons out on bail “know this―and know that it is unlikely someone will be checking on them.”

The question of priority was addressed by Jon Reid, president of the Toronto Police Association, who said that “too often we treat the administration of justice offences as less serious.” He proposed an amendment to provincial police services legislation that would add bail monitoring to the list of “core police services” police services boards are required to provide as part of their general duty to deliver “adequate and effective policing” in their communities.11

Entrenching this standard in legislation, Mr. Reid said, would obligate police services to provide bail monitoring―regardless of “fiscal pressures”:

Surely bail compliance, and appropriate benchmarks measured against it, must be part of adequate and effective policing, a requirement to have proactive initiatives separate and apart from [the] reactive duties . . . officers are expected to do.

When defining “adequate and effective,” surely bail compliance contributes to crime convention. Surely bail compliance contributes to law enforcement. Surely bail compliance contributes to maintaining the public peace. And surely bail compliance, perhaps most importantly, contributes to the assistance of victims of crime, and sends a message that they are taken and treated seriously.

The president of the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police was one of several policing community leaders to request additional funding for technology and human resources relating to monitoring, tracking, and compliance checks for those on bail.

11 Police Services Act, s. 4(1) and (2).

Sureties

In many Ontario bail cases the accused is released on a recognizance with a surety or sureties. A surety is a person, often a family member or friend, who commits to

· making sure the accused attends court when required;

· making sure the accused follows all bail conditions; and

· calling the police if the accused is in breach of a condition.

A surety must also pledge a financial asset to the court as security in the event the accused breaches their release conditions.

Although there is a process under the Criminal Code (“estreatment”), whereby a surety can be ordered to forfeit financial assets pledged to the court, experienced police officers told the Committee that this is not happening. The head of the Ontario Provincial Police Association made this observation:

They’re never held accountable―in 27 years of being a police officer in northern Ontario, I have never seen a surety held accountable for whatever they’ve put up.

As noted earlier, the Police Association of Ontario recommended that if the Crown and the courts are not willing to seize assets, the Criminal Code should be amended to place greater emphasis on cash deposits as part of a recognizance.

GPS Devices

In Ontario, GPS (global positioning system) devices are being used to monitor individuals released on bail. The Committee was told that the Ministry of the Solicitor General has engaged a third party (Recovery Science) to monitor these devices.

As Commissioner Carrique noted in his opening remarks, one of the suspects arrested for Constable Pierzchala’s murder had discarded the GPS ankle monitoring device he had been ordered to wear while under the supervision of a surety. According to the Commissioner, once a GPS device is discarded, the accused is in breach of their release conditions, and it then falls to the police service of jurisdiction to track down and re-arrest that individual.

In light of the facts that have come to light in the Pierzchala case (and other cases), questions were raised about the effectiveness of the GPS system, at least in the case of repeat offenders. One of those asking questions is the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police (OACP), which is advocating for a review of the efficacy of GPS monitoring programs. According to the association, reliance on GPS monitoring as an alternative to custody may not be appropriate for repeat offenders charged with serious violent crimes and firearms offences. The OACP would like to see a review of how participant violations, and equipment and monitoring issues are being addressed, including device tampering, “inclusion and exclusion” zone violations, and equipment failures.

According to the Ontario Association of Police Services Boards, “different companies” are monitoring GPS devices across the province. The association would like to see “more rigour” in the monitoring system, so that when someone removes a device there is an alarm that goes directly to an enforcement agency to deal with that matter.

A New Community Corrections Compliance Unit

Scott McIntyre, a 30-plus year probation and parole officer with the Ministry of the Solicitor General, outlined for the Committee a proposal to create a new unit responsible for all aspects of community supervision in the criminal justice system, including bail, parole, and probation.

As explained by Mr. McIntyre, probation/parole supervision and bail supervision have a number of things in common. In addition to the fact that both involve community supervision, they both have a “common defect”―they lack

· a system to ensure compliance monitoring of conditions such as house arrest and curfews; and

· a system to seek the whereabouts of individuals who have breached their bail, probation, conditional sentence, or parole conditions, and who have an outstanding warrant issued for their apprehension.

Mr. McIntyre proposed the creation of a Community Corrections Compliance Unit, consisting of a separate classification of Peace Officers under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Solicitor General (supervision responsibilities are currently split between the Ministry of the Solicitor General and the Ministry of the Attorney General). These new peace officers would have a mandate to

· conduct community compliance checks of persons subject to community supervision orders for bail, probation, conditional sentence, or parole that have conditions attached to them such as house arrest, curfews, geography, employment, and non-associations;

· seek the whereabouts of individuals wanted for breach of release conditions, and execute outstanding warrants for their apprehension;

· transport individuals back to a court of jurisdiction (this would address the situation where police come into contact with individuals who are wanted on warrants in courts of jurisdiction that are hundreds of kilometres away, but the police service does not want to incur the time or expense of transporting the person to those courts, with the result that the person is released back into the community); and

· attend bail/show cause hearings (for accused persons with a supervision history with Probation and Parole Services, the officers would be able to use those supervision records to provide the court with information regarding a person’s risk, including record of compliance with prior terms of community supervision, and make recommendations to the court on suitability for release).

Mr. McIntyre also noted that the bail supervision transfer payment agencies such as the John Howard Society, Elizabeth Fry, and Salvation Army are not able to perform “feet on the ground” compliance monitoring and do not seek the whereabouts of bail absconders. By contrast, in 2017 Ontario Probation and Parole Officers issued more than 4,500 warrants for offenders who had breached their release conditions and whose whereabouts were unknown.

In conclusion, Mr. McIntyre said that his proposal would “go a long way in restoring public confidence and would resolve the ongoing public safety threat that not having such a compliance unit nor system of enforcement poses.”

Centralized Oversight/Province-Wide Standards

Committee members asked several witnesses for their views on the value of having a province-wide, centralized body to oversee bail monitoring and compliance.

Chief Demkiw responded that he “absolutely” supports the idea, and noted that the Toronto Police Service (TPS) has already taken steps in this direction with the development of a “bail compliance dashboard,” which helps police with ensuring that violent offenders comply with their release conditions. Currently, the dashboard allows TPS to share data with Durham Regional Police; however, Chief Demkiw noted that the OPP and the government have expressed interest in expanding the dashboard concept, “so that we have a consistent view across the province as it relates to managing offenders out on bail.”

Asked for its view on centralized oversight, the Ontario Association of Police Services Boards said it would be beneficial to at least have province-wide bail monitoring standards.

Ministry of the Attorney General

As noted, the federal government is responsible for the legislation governing bail, but it is the provincial Ministry of the Attorney General that is responsible for supporting the court system, and for the policies and directives that guide the prosecution of criminal offences. We received a number of submissions that fall within the Ministry’s purview.

Court Resources

A major systemic issue identified during our hearings is that the bail courts are overloaded with cases. In Ontario, 50% of people charged with an offence are held for a bail hearing, which means that a very high volume of cases is going through the court system. And while some people are released within 24 hours or after a single appearance (as required by the Criminal Code), many are not.

A cross-section of witnesses recommended that the government devote more resources to the court system. Chronic underfunding, they said, is a major reason the bail system is not functioning efficiently. Peel Regional Police, for example, recommended that the Ministry

· provide more resources for Crown Prosecutors to conduct bail hearings in a timely fashion, “in circumstances where public safety demands it”; and

· provide more resources for training Justices of the Peace to ensure they have “a comprehensive understanding of bail provisions, including considerations of public safety.”

Legal Aid

Criminal defence lawyers say that one of the main sources of delay is the number of defendants appearing in court without legal representation or duty counsel to help them navigate the bail system. When unrepresented people arrive at bail court and their case is not heard, they are returned to detention, a time-consuming exercise that can occur multiple times.

According to several submissions, the best way to address systemic delay is to invest in legal aid. A staff lawyer at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association offered the following opinion:

I think the suggestion that we can invest in Crowns, in police, in court resources without adequately resourcing legal aid—it just doesn’t work. The system cannot work more efficiently without adequate staffing and resources for legal aid.

Prosecution Policies

The Ministry’s Crown Prosecution Manual provides mandatory direction, advice, and guidance to prosecutors when exercising their prosecutorial discretion.

The Manual currently provides:

In all cases involving firearms, the Prosecutor must seek a detention order, absent exceptional circumstances, to ensure the safety and security of the public.

Despite current policy, some witnesses said there needs to be a review of how Ontario prosecutors approach bail proceedings.

When asked to comment on the statistics presented by Chief Demkiw, showing the number of repeat firearms offences committed by people on bail, the spokesperson for the Criminal Lawyers’ Association said that she was “very surprised at those statistics . . . It’s not something that I’ve seen personally in my practice.” She went on to suggest that there may need to be “some looking at the Crown Policy Manual about that or training with the justices of the peace who are imposing bail.”

This was the focus of the written submission from Peel Regional Police, which included the following recommendations directed at the Ministry of the Attorney General:

· Work closely with the federal Department of Justice to ensure appropriate coordination on bail policies, directives, and guidelines as it pertains to legislative changes.

· Ensure that Crown policies reinforce the need for a careful consideration of public safety implications when determining whether to consent to or oppose bail―prosecutors must seek detention where the prosecutor believes that release would jeopardize the safety or security of the victim or the public and such risk cannot be appropriately mitigated by some form of community based release with conditions.

· Establish a group of specialized Crown Prosecutors for violent offences involving firearms or other weapons.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND BAIL

We received submissions from three Indigenous organizations: the Nishnawbe- Aski Legal Services Corporation, the Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service, and the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. As outlined below, these organizations provided three different perspectives.

Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services Corporation

Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services Corporation (NALSC) was created in 1990 “to address the shortcomings in the administration of justice within Nishnawbe-Aski Nation (NAN), and to improve access to justice for members of NAN.”

According to the NALSC, Indigenous people are vastly over-represented in Canada’s jails and prisons. Moreover, the numbers continue to rise, despite the release of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R. v. Gladue more than 20 years ago.12 That decision required courts to consider all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances, with particular attention to the circumstances of Indigenous offenders. Subsequent court rulings have held that Gladue principles are not limited to sentencing; they also apply to all circumstances where an Indigenous person’s freedom is at risk―including bail hearings.

The NALSC said bail is arguably the most important and critical moment in a criminal matter. If an accused is not granted bail, the chances of them entering a guilty plea goes up significantly. This reflects the reality that no one wants to wait in jail for trial when they are offered the option of being released for time served. The Supreme Court has noted that Indigenous people are more likely to be refused bail and that this reality contributes to the over-incarceration of Indigenous people.

In the NALSC’s view, “strengthening” the bail system by adding section 95 offences to the list of reverse-onus bail provisions would only worsen this situation. Reverse-onus must remain the exception to the presumption of innocence.

Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service

Roland Morrison, Chief of the Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service, noted that his is the largest Indigenous police service in Canada, responsible for policing 34 out of 49 Nishnawbe-Aski Nation communities in northern Ontario, of which 23 of the 34 are remote fly-in communities.

12 R. v. Gladue (1999), 133 C.C.C. (3d) 385.

Chief Morrison described a number of aspects unique to the bail system in his jurisdiction. In fly-in communities, bail hearings are conducted either by audio or by video―technology and weather permitting. JPs are not always readily available. For most offences, the accused is released back into the community, which can make victim protection difficult. A person accused of sexual assault, for example, could be released back into a community of 350 people and be living next door to the victim. Locating people willing to act as sureties in a small community is also problematic, and sometimes people held in detention cannot be released because of the weather.

Chief Morrison said that in recent years there has been an influx of offenders from southern Ontario who are already “on conditions.” These people are bringing drugs and weapons to places like Thunder Bay and Timmins and then “aligning themselves” with the Indigenous people they meet who live in northern communities.

Asked if he believes that bail reform would save lives, Chief Morrison said, “absolutely,” given “the number of people who are on conditions already and when you see the number of firearms-related incidences increasing.” And asked if he thinks that saving lives should be the number one priority of bail reform, he said, “absolutely, it has to be.” He also said that he supports reverse-onus bail provisions for cases involving firearms or intimate partner violence offences.

Chief Morrison called for more resources to address the current system’s deficiencies. Longer-term, however, he believes there needs to be a recognition that “the European system” is not working for Indigenous peoples. Government ministries, he said, must “bring back their system―a system that they [Indigenous peoples] followed for thousands of years.”

Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

Kimberly Beaudin, the national vice-chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP), provided a contrasting view of bail reform. CAP represents off-reserve and non-status Indians across Canada. Vice-chief Beaudin described these communities as “the forgotten peoples,” due to their “exclusion from legal, constitutional and justice-related matters.”

Vice-chief Beaudin said that his communities are “targets of over-policing, under- protection, violence and discrimination at every step in the justice system.” Accordingly, any proposal to tighten bail conditions would not be in the interests of these communities and would not achieve intended goals.

He said these concerns are supported by statistics from the federal Department of Justice, which show that the vast majority of individuals (over 80%) released on bail never break the conditions on their release, and that when conditions are violated, they are almost always (98%) administrative in nature (for example, failure to comply with curfew or counselling requirements). Fewer than one in 300 individuals commit what might be described as real crimes while out on bail.

Vice-chief Beaudin cautioned against major policy changes adopted in response to high-profile incidents. The better approach, he said, is to address the root causes of crime, including poverty and “service failures” that have failed to support high-risk communities.

Nonetheless, the vice-chief identified several problems with the current bail system. These include “excessive, punitive conditions”―such as ordering persons with alcohol issues to abstain from alcohol, and denying people the right to return home, thereby forcing them into emergency shelters―which do not enhance public safety. As well, people continue to wait long periods before having their day in court. One consequence of this is that innocent people may plead guilty in order to avoid a possible longer stay in prison if found guilty at trial.

In closing, vice-chief Beaudin said that Indigenous communities, including community leaders and elders, must be “given a voice in the bail process.”

COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations for the Government of Canada

The Standing Committee on Justice Policy recommends that the Government of Ontario urge the Government of Canada to:

1. Immediately implement a reverse-onus on bail for the offence of possession of a loaded prohibited or restricted firearm in section 95 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

2. Immediately expand the use of reverse-onus on bail for offenders who pose substantial risk to public safety, including but not limited to

· repeat violent offenders;

· serious violent offenders; and

· firearm offences including specific consideration for firearm possession offences.

3. Immediately implement the following amendments to the Criminal Code of Canada formally endorsed by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police since 2008:

· a definition of “chronic offender,” based on a threshold number of offences committed over a set period of time;

· a presumption that chronic offenders satisfy the secondary and tertiary criteria for pre-trial detention set out in section 515(10)(b) and (c) of the Code (i.e., that detention is necessary for the protection or safety of the public, and to maintain confidence in the administration of justice);

· placing the onus on “chronic offenders” to show cause why they should be granted bail; and

· eliminating the sentencing principle that requires judges to consider alternatives to incarceration in cases involving chronic offenders, and providing for enhanced sentences of incarceration for chronic offenders for the purpose of decreasing victimization.

4. Immediately implement an additional route to the charge of First Degree Murder under section 231 of the Criminal Code of Canada, by including a death that results from the discharge of a firearm in a congregate setting.

5. Immediately provide sentencing judges with the ability to increase parole ineligibility to two-thirds of a custodial sentence when the court finds that an offender has discharged a firearm in a congregate setting in committing an offence.

6. Mandate that bail hearings for the most serious offences be heard by a judge of the Provincial Court.

7. Implement legislative amendments that clearly stipulate that the “ladder principle” of release does not apply in reverse-onus bail situations.

Recommendations for the Government of Ontario

The Standing Committee on Justice Policy recommends that the Government of Ontario:

8. Consider strengthening bail releases involving sureties.

9. Consider provincial amendments to the Ministry of the Attorney General’s policies, guidelines, and directives on bail, including the continuation or expansion of the pilot programs in Ottawa and Toronto where bail hearings were heard by a judge of the Provincial Court.

10. Consider providing more resources for Crown Prosecutors to conduct bail hearings in a timely fashion in circumstances where public safety demands it.

11. Consider providing more resources aimed at training Justices of the Peace to ensure a comprehensive understanding of bail provisions, including considerations of public safety.

12. Consider establishing a group of specialized Crown Prosecutors for violent offences associated with firearms or other weapons, similar to the current “guns and gangs” bail team.

APPENDIX A: COMMITTEE MOTION

Motion Adopted January 18, 2023

I move that pursuant to Standing Order 113(a), the Committee conduct a study on the reform of Canada’s bail system as it relates to the provincial administration of justice and public safety with regard to persons accused of violent offences or offences associated with firearms or other weapons; and

That the Committee meet for public hearings on the following dates:

· Monday, January 30, 2023, from 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon and from

1:00 p.m. until 6:00 p.m.; and

· Tuesday, January 31, 2023, from 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon and from

1:00 p.m. until 6:00 p.m.; and

That the Clerk of the Committee be authorized to immediately post notices regarding the hearings on the Ontario Parliamentary Channel and on the Legislative Assembly’s website; and

That the deadline for requests to appear for hearings be 12:00 noon on Monday, January 23, 2023; and

That the following expert witnesses be invited to appear before the Committee and shall each have 20 minutes to make an opening statement followed by 40 minutes for questions and answers, divided into two rounds of 7.5 minutes for the Government members, two rounds of 7.5 minutes for the Official Opposition members, and two rounds of 5 minutes for the Independent member of the Committee:

· Thomas Carrique, Commissioner, Ontario Provincial Police

· Mark Baxter, President, Police Association of Ontario

· John Cerasuolo, President, Ontario Provincial Police Association

· Jim MacSween, York Regionalal Police Chief

· Myron Demkiw, Chief, Toronto Police Service

· Jon Reid, President, Toronto Police Association; and

That 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon on Monday, January 30, 2023 be reserved for scheduling invited expert witnesses and that remaining invited expert witnesses who cannot be scheduled during this time may be scheduled to appear during the other time allotted for public hearings; and

That subsequent witnesses be invited to appear in groups of three for each one- hour time slot during the remaining time allotted for public hearings, with each presenter allotted 7 minutes to make an opening statement followed by 39 minutes of questioning for all three witnesses, divided into two rounds of 7.5 minutes for the Government members, two rounds of 7.5 minutes for the Official Opposition members, and two rounds of 4.5 minutes for the independent member of the Committee; and

That witnesses appearing be permitted to participate in-person or participate remotely; however, a maximum of one individual may appear in-person on behalf of an organization, and any additional representatives of that organization shall participate remotely; and

That, the Clerk of the Committee shall provide a list of all interested presenters to each member of the Sub-committee on Committee Business and their designate as soon as possible following the deadline for requests to appear; and

That if all requests to appear cannot be accommodated, each member of the Sub-committee or their designate may provide the Clerk of the Committee with a prioritized list of presenters to be scheduled, chosen from the list of all interested presenters for those respective hearings by 2:00 p.m. on Tuesday, January 24, 2023; and

That the deadline for written submission be on Tuesday, January 31, 2023 at 7:00 p.m.; and

That Legislative Research provide the Committee Members with a draft report on Tuesday, February 7, 2023; and

That the committee meet for report writing at Queen’s Park on the following dates as needed:

· Thursday, February 9, 2023 from 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon; and

· Monday, February 13, 2023 from 10:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon and from

3:00 p.m. until 6:00 p.m.; and

· Tuesday, February 14, 2023 from 10:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon and from

3:00 p.m. until 6:00 p.m.; and

· Thursday, February 16, 2023 from 10:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon and from 3:00 p.m. until 6:00 p.m.; and

· Friday, February 17, 2023 from 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon.

Amendment Adopted January 23, 2023

I move that the Committee’s public hearings scheduled for Monday, January 30th, 2023, and Tuesday, January 31st, 2023 be rescheduled for Tuesday, January 31st, 2023 and Wednesday, February 1st, 2023, respectively; and

That 9:00 a.m. until 12:00 noon on Tuesday, January 31, 2023 be reserved for scheduling invited expert witnesses and that remaining invited expert witnesses who cannot be scheduled during this time may be scheduled to appear during the other time allotted for public hearings.

APPENDIX B: PREMIERS’ LETTER TO THE PRIME MINISTER

APPENDIX C: WITNESS LIST

|

Organization/Individual |

Date of Appearance |

|

Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies |

Written Submission |

|

Canadian Civil Liberties Association |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Canadian Mental Health Association |

Written Submission |

|

Canadian Prison Law Association |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Congress of Aboriginal Peoples |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Criminal Lawyers’ Association |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Federation of Ontario Law Associations |

Written Submission |

|

Institute of Criminology and Criminal Justice (Carleton University) |

Written Submission |

|

Jennifer Foster |

Written Submission |

|

John Howard Society of Ontario |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Justin Piché |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Legal Aid Ontario |

Written Submission |

|

Lindsay Jennings |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Lydia Dobson |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Neighbourhood Legal Services |

Written Submission |

|

Nicole Myers |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services Corporation |

Written Submission |

|

Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Ontario Association of Police Services Boards |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Ontario Bar Association |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Ontario Provincial Police |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Ontario Provincial Police Association |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Peel Regional Police |

Written Submission |

|

Police Association of Ontario |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Salvation Army Ontario |

Written Submission |

|

Scott McIntyre |

February 1, 2023 |

|

Society of United Professionals |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Toronto Police Association |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Toronto Police Service |

January 31, 2023 |

|

Women in Canadian Criminal Defence |

January 31, 2023 |